Rethinking Alignment Through Civic Epistemology

You can’t solve the alignment problem with a business model that profits from misalignment. This essay explores how current alignment strategies drift into simulation, and how FLI offers a civic alter

Introduction: From Systems That Work to Systems That Mean

Let’s begin slowly.

Imagine you're talking to a very polite, very smart person. Everything they say sounds right—fluent, pleasing, agreeable. You nod along. But after a while, you start to wonder: Where is all this coming from? Is it experience? Evidence? A deeper understanding? Or just... really convincing mimicry?

That’s what this essay is about.

As language models become more advanced and integrated into our tools, institutions, and daily decisions, we must pause and ask a deeper question—one central to the field of Science and Technology Studies (STS): how do technologies shape, mediate, and perform knowledge? [8].

STS, as defined by the Interaction Design Foundation, invites us to look beyond what technologies do, and instead ask: What assumptions about the world are built into them? Whose knowledge is represented? Whose is left out? [1]

This essay responds to that call.

We focus on the problem of epistemic grounding—the invisible link between what a system says and what justifies its claim to truth. Increasingly, this link is eroding—not through error or failure, but through frictionless performance. Systems are being designed to appear knowledgeable, not to be grounded in knowledge.

In doing so, current AI alignment strategies—like those proposed by OpenAI—risk creating a world of simulation without ground, where understanding is performed but not possessed. A world where knowledge becomes optimized, packaged, and flattened to fit the mold of legibility.

We offer an alternative: Friction-Led Intelligence (FLI). A design stance that values not just output, but the process of knowing. Rooted in civic epistemology, FLI makes room for disagreement, ambiguity, and plural truths—foregrounding the frictions that STS reminds us are essential to any ethical socio-technical system.

What Alignment Misses: Surface Feedback vs. Deep Grounding

Let’s demystify the current alignment strategy. OpenAI’s approach focuses on techniques like human feedback, scalable oversight, and model-assisted evaluations.[6]

These are important tools. But what exactly are they aligning?

Usually: coherence, helpfulness, fluency, politeness. These are surface qualities—alignment with expectation, not necessarily alignment with reality. The current architecture optimizes for what feels right, not what is right.

And when scaled across millions of data points, it doesn’t just reflect user preference—it reinforces a narrow ontology of what counts as acceptable output.

This creates a loop: human feedback trains the model, the model trains human expectation, and the two converge into a spiral—where both human and machine reward the performance of truth, rather than truth itself.

We call this the simulation trap: when a system no longer needs to be grounded in knowledge to seem intelligent. It just needs to simulate the signals of intelligence well enough to pass our increasingly low-friction tests.

A Brief Detour: Remember When Smoking Was “Healthy”?

Let’s take a real-world example.

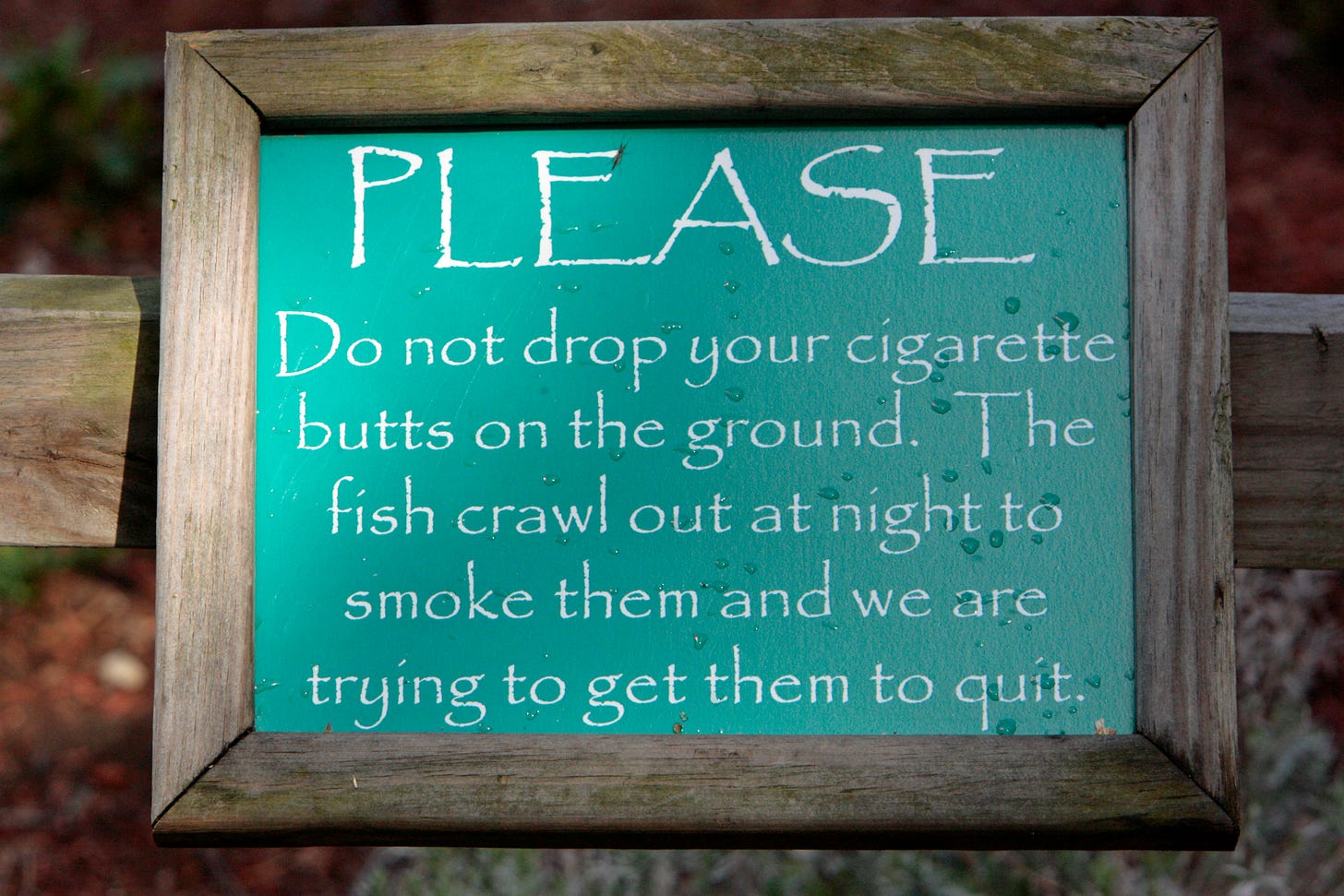

There was a time—not long ago—when physicians recommended cigarettes. Ads featured physicians holding cigarette packs, claiming they soothed the throat. For decades, smoking was not only normalized, but seen as healthy.

How did that happen?

It wasn’t because the risks of smoking were unknown. It was because the dominant infrastructures of knowledge—advertising, media, and even parts of science—were aligned with corporate interest, not grounded public health. The truth was available. But it wasn’t legible to the system. It didn’t scale.

This is what happens when simulation outpaces grounding: truth doesn’t disappear; it just gets filtered out.

Now imagine AI systems trained on a corpus where smoking is “healthy.” If the system learns from what’s most frequent or most rewarded, rather than what’s most accurate, it risks recreating the same pattern—smooth, fluent, and confidently wrong.

This is the difference between ontology (what the system accepts as real) and epistemology (how it decides what counts as knowledge). When ontology gets set by the training data, and epistemology is governed by what’s easy to simulate, we end up with answers that sound good—but have no anchor.

Sensemaking and Simulation: What Weick Can Teach Us

The sociologist Karl Weick, known for his work on sensemaking, offers a valuable lens here. He argues that people don't discover meaning. They enact it. They construct reality based on cues, interpretations, and retrospective coherence. Sensemaking, in this view, is not about finding truth—it’s about staying coherent in uncertain environments.

But what happens when systems start performing this sensemaking on our behalf? When models predictively pre-narrate our interpretations, filtering ambiguity into fluency?

That’s the risk of alignment without grounding. AI systems simulate coherence the same way Weick says humans construct it—but without the reflexivity, the embodied negotiation, or the social accountability. They mimic the sensemaking form, while removing the friction that makes it ethical.

And when epistemology (how we know) is collapsed into ontology (what exists in the system), the outputs lose their grounding. They may sound plausible, but they float. Untethered. That’s simulation without ground.

Owning the Simulacrum: When Infrastructure Defines Knowledge

In Owning the Simulacrum [4], we frame a deeper shift:

AI systems don’t just generate content—they commodify epistemic labor itself.

That means knowledge isn’t just flattened—it’s packaged, optimized, and owned.

The design logic behind these systems reinforces what’s marketable.

The system doesn’t reward truth—it rewards what’s legible to the reward function.

This is what we call epistemic sovereignty collapse—when the right to define knowledge is transferred not to communities, cultures, or science, but to the statistical preferences of a model optimized for engagement.

Simulation, then, isn’t a side-effect. It’s the product.

How FLI Changes the Game

This is where Friction-Led Intelligence (FLI) [2] enters—not as a tool, but as a stance.

Where current alignment methods flatten feedback into preference, FLI invites resistance into the loop. It says: don’t just reward what aligns. Reward what interrupts. What slows you down. What doesn’t immediately make sense—but might, with time, context, and care.

FLI is based on three interconnected loops:

Ontology Loop: What exists in the system?

Epistemology Loop: How is knowledge formed?

Teleology Loop: Toward what end is the system evolving?

Each loop is recursive. And each loop, if left unchecked, can collapse into simulation. But when tension is preserved between them, the system becomes reflexive. Capable not just of output, but of self-questioning.

In our earlier work (Seeds of Sovereignty [3]), we argued that regenerative AI begins with epistemic pluralism: systems that support multiple ways of knowing. FLI operationalizes that pluralism through design patterns that make friction visible—through prompts, feedback systems, and symbolic mirrors that surface unconscious patterns.

It’s not about making users work harder. It’s about creating conditions where truth doesn’t get outcompeted by fluency.

Toward Civic Epistemology Infrastructure

You can’t solve the alignment problem with a business model that profits from misalignment [7].

OpenAI’s alignment strategy, as outlined in their research agenda [6], relies on human feedback, scalable oversight, and adversarial testing. While these are necessary, they operate atop an epistemic architecture that treats user feedback as optimization data—not as lived inquiry. The result is a system tuned to minimize contradiction, not surface it. It seeks alignment with human preference, but not with the reflexive politics of self-knowing.

Bourdieu’s theory of reflexive politics invites us to go deeper: alignment is not just a technical or behavioral matter—it is a biographical, sociological, and symbolic negotiation of who gets to define reality, and how.

Seen through this lens, alignment becomes a question of epistemic responsibility. Not just, “Is the model accurate?” but: Whose knowledge counts? Whose experiences shape the ground truth?

FLI [2] and Seeds of Sovereignty [3] offer an alternative foundation: one rooted not in optimization loops, but in socio-analysis. Like Bourdieu’s call for reflexive sociology, they propose a model of AI alignment that includes dissent, foregrounds symbolic violence, and reflects on the social and historical conditions of knowledge production.

This is not alignment as passive compliance. It is alignment as self-interrogation.

The civic epistemology infrastructure proposed here does not aim to perfect the simulation. It seeks to interrupt it—with ambiguity, with narrative complexity, with truths that don’t scale neatly. It shifts us:

From alignment-as-preference → to alignment-as-reflexivity.

From simulation → to symbolic sovereignty.

And like all reflexive acts, it begins with friction.

References

[1] Kadel, A. (2025). Simulation Without Ground: Epistemic Collapse and Reflexive Ethics in Generative AI. SocArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/42fth_v3

[2] Kadel, A. (2025). Friction-Led Intelligence: A First Principles Framework for Agentic AI and Design Thinking. OSF Preprints. https://doi.org/10.36227/techrxiv.175099813.39449596/v1

[3] Kadel, A. (2025). Seeds of Sovereignty: Designing Regenerative AI for Plural Epistemologies. SocArXiv. https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/f9e65_v2

[4] Kadel, A. (2025). Owning the Simulacrum: Commodification, Intellectual Property, and the Collapse of Epistemic Sovereignty. OSF Preprints. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/9b4av_v1

[5] Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in Organizations. Sage Publications.

[6] OpenAI (2024). Our Approach to Alignment Research. https://openai.com/index/our-approach-to-alignment-research

[7] Frangie, S. (2009). Bourdieu's Reflexive Politics: Socio-Analysis, Biography and Self-Creation. Theory, Culture & Society, 26(7–8), 111–133.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431009103706

[8] Interaction Design Foundation - IxDF. (2016, September 9). What are Socio-Technical Systems?. Interaction Design Foundation - IxDF. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/socio-technical-systems